Modern Map of the World

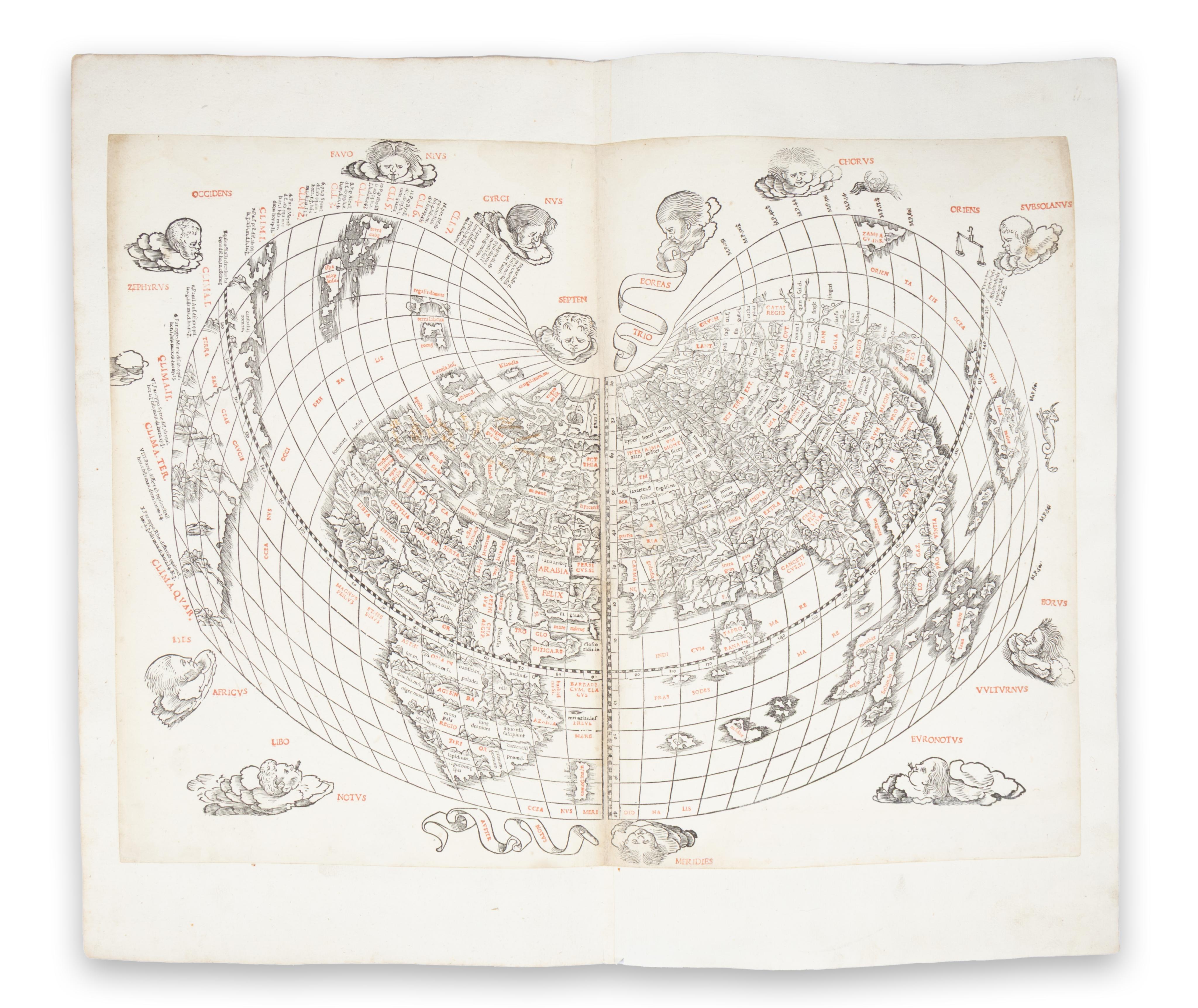

1511, Venice.Bernardus Sylvanus' pseudo–cordiform map of the modern world, published in Venice in 1511, is a work of landmark importance. It stands as the second atlas map of the world to depict America, predated only by Johann Ruysch's map of 1507. It is also the earliest obtainable printed map to display and name the island of Japan.

This world map is one of the earliest obtainable examples to include a portion of America, a mere twenty years after Columbus' discovery of the New World. It is also one of the earliest world maps printed in Venice and the first to be printed in two colors. A printing error in Asia – the duplication of the place name "come" in both red and black – reveals that the color was applied using separate registers.

Sylvanus' world map was included in the 1511 edited edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. Usually placed at the back of this volume, a few copies have also been found on vellum. However, the map was never reprinted, and so is extremely rare on the market.

In his dedication to Andreas Matheus Aquaevivus, Duke of Adria and Lord of Eboli, Sylvanus lamented that Ptolemy's charts did not reflect the experiences of modern sailors. Sylvanus constructed this map in an attempt to reconcile and improve upon Ptolemy's worldview by integrating new information as Europeans were coming to know the world at the start of the 16th Century.

The landmasses are vigorously engraved with mountain ranges, rivers, and place names. A dozen decorative windheads and three signs of the zodiac surround the map: Cancer and Capricorn for the tropics, and the scales of Libra representing the equator. The sides are embellished with information on climates, with seven climates (represented as windheads) recorded above the equator and four below. Latitude spans from eighty degrees north to forty degrees south, while longitude is 320 degrees wide, though the numbering suggests Sylvanus believed there was more global space than he chose to show.

Sylvanus' map integrates a considerable amount of modern data. The Indian Peninsula, the British Isles, and Africa all reflect the work of modern cartographers. Scotland is situated north of England and Wales rather than extending horizontally east as it did in Ptolemy's maps. Furthermore, there is no strip of land connecting southern Africa with Asia, making Africa circumnavigable.

Asia presents a mixture of old and new. A large peninsula remains in Southeast Asia, a holdover of Ptolemy's Afro–Asian bridge that made the Indian Ocean an insular sea. However, the islands "Java Minor" and "Java Maior" appear, resulting from the dissemination of Marco Polo's travels. This makes the region a synthesis of ancient and recent sources. Due to a scribal error, "Java Minor" was substituted for Champa, leading 16th–century mapmakers to locate the lesser Java over a thousand miles from "Java Maior." The latter became associated with Terra Australis and was thought to be part of a huge southern continent.

Near the eastern border of the projection lies the island of "Zampagv" (Japan). This is only the second printed map to include Japan and the first time it appeared in an edition of Ptolemy's works. The first appearance was on the Contarini/Rosselli map of 1506, of which only one copy is known. Sylvanus' "Zampagv" is similar in shape to an unnamed island on the Ruysch world map of 1508. Ruysch did not label Japan, explaining that he thought Hispaniola was likely Japan, but he left an unlabeled island west of Hispaniola as an alternative. Sylvanus adopted the shape of that unnamed island as his Japan but correctly moved it from the Caribbean to the Far East.

Although partial and somewhat speculative, Sylvanus' depiction of the Americas is important as it presents a fascinating view of the post–Columbian world. South America is named "Terra Sanctae Crucis," and its only label refers to cannibals, "canibalis roman." This is likely meant to be "canibalis comon," after a description in the Ruysch map of 1508, or "canibaluz domon," domain of the cannibals. An undefined coastline at the extreme south suggests a southern continent or island, which would reconcile part of Ptolemy's map – a southern land formed of the Afro–Asian land bridge – with this updated version of the world. Similarly, Sylvanus leaves the coasts unfinished in the Americas and eastern Asia, allowing for the possibility that those continents might connect.

To the north lie the island "terra laboratorus" and a region named "regalis domus," an inverted Latinization of "corte real" or royal court. Together, these are among the earliest appearances of the northeastern North American coast on a printed map. "Terra laboratus" is attributed to the Portuguese–Azorean navigator Joao Fernandes, but the placement suggests the mapmaker thought Fernandes had located Greenland, not an island farther west. "Regalis domus" represents the explorations of Gaspar and Miguel Corte Real in 1501. The brothers made contact with indigenous peoples, but Gaspar's ship disappeared, and Miguel also vanished when he returned to look for his brother. Most contemporary maps use "terra corte real" after the brothers, yet Sylvanus chose "regalis domus" (royal house). As Don McGuirk argues, this may be because Sylvanus was aware that John Cabot, an honorary Venetian employed by the English Crown, had made similar discoveries several years earlier. As a Venetian himself, Sylvanus may have wanted to leave the attribution of the land open to either Portugal or England, both royal houses.

The final lands in the Americas are "terra cuba" and "Ispania insu." The latter refers to Hispaniola, comprised today of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. "Terra cuba" is Cuba, which Columbus was convinced was the coast of Asia because he thought it too long to be merely an island. The use of "terra" instead of "insula" may imply that Sylvanus agreed with Columbus, or at least thought there was more to find in the area. As a whole, the map offers a window into how geographers were reconciling old theories with new information, portraying a Europe looking both east and west.

Map slightly trimmed, not affecting image. Mounted on paper. Lower right corner expertly restored, not affectin the engraving. Some negligible discoloring do to age along the fold and the upper margin. Overall a beautiful copy.

Poss.: On the verso is the dry collection blind stamp of the renowned map historian László Gróf( 1933-2020). He fled Hungary in the 1956 anti-Soviet Revolution, and settled in Oxford. After moving to England, he began collecting old maps of historical Hungary, establishing the Carta Hungarica map collection. He joined the Hungarian Philatelic Society of Great Britain in its founding year in 1964, and was a prominent member onward.

Reference: Shirley 31